Caselaw Update: Adverse Possession of Public Land?

Posted Friday, November 19, 2021 by Christopher L. Thayer

Caselaw Update: Adverse Possession of Public Land?

Court reaffirms common law doctrine of nullum tempus occurrit regi.

In Michel v. City of Seattle (No. 82073-7-1, 11.8.21), the Washington Court of Appeals, Division I, recently addressed the issue of whether or not it is possible to adversely possess public property owned by a municipality and the old common law doctrine known as nullum tempus occurrit regi (no time runs against the king), which has been codified into statute in Washington. At issue in Michel, was whether plaintiffs could adversely possess property owned by the City of Seattle, which the homeowners alleged was used for non-governmental proprietary purposes.

The facts of Michel are as follows:

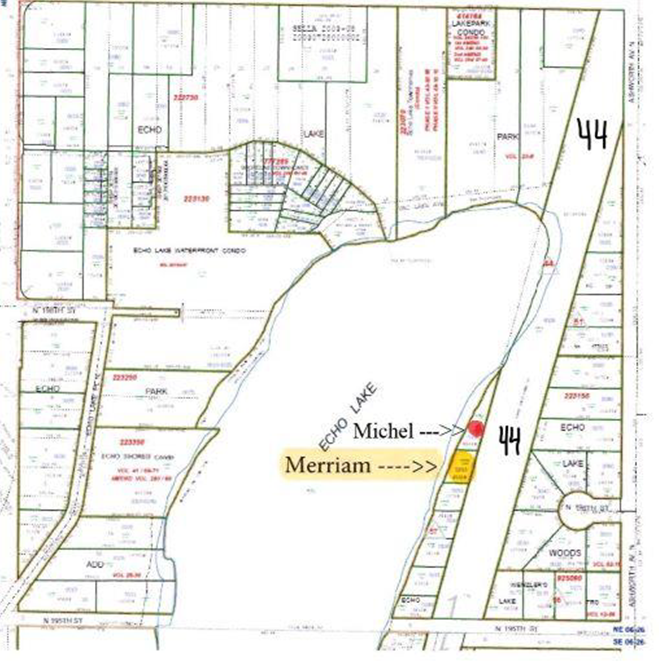

In the early 1900s, the Wenzlers and the Mehlhorns owned tract 44, a long,100-foot-wide lot adjacent to Echo Lake in Shoreline, as appears below. In 1905, they executed a “right of way deed” in favor of the Seattle-Everett Interurban Railway Company, letting it use tract 44 as a railway. If tract 44 stopped being used as a railway, then ownership would revert to the original owners and their heirs or assigns. Over the next 25 years, ownership of tract 44 changed numerous times. In 1939, it stopped being used as a railway. In 1945, it was conveyed to the Puget Sound Power & Light Company. And in 1951, Puget Sound Power & Light conveyed tract 44 to the City, which managed the tract through Seattle City Light.

By 2018, the lots adjacent to tract 44 had been subdivided and developed. Married couples, the Michels and the Merriams (homeowners), lived on neighboring lots between Echo Lake and tract 44. The homeowner’ fenced front yards, the disputed properties, are located on tract 44. The nearest street runs along tract 44.

A map of the parcels helps identify the homeowners’ predicament:

The City of Seattle demanded plaintiffs remove their fence from tract 44, which they refused to do. The City then removed the fence, and litigation ensued.

Initially, the court had to deal with the City’s own adverse possession claim. In light of the right of way deed restriction, title to tract 44 should have reverted to the prior owners once/if the tract was no longer used as a railroad. The City presented evidence it had used tract 44 since 1951 for electrical distribution with power poles. The trial court ruled the City had adversely possessed Tract 44 by 1961. The homeowners claimed the City had not established it had adversely possessed their fenced yards, which encroach into tract 44 – because “the City never established exclusive possession of the portions of [tract[ 44 occupied by Michels … and their predecessors because it never possessed the area inside the [homeowners’] fence line.” The Court of Appeals disagreed.

A person claiming adverse possession must prove they possessed the property for at least 10 years in a manner that is (1) open and notorious, (2) actual and uninterrupted, (3) exclusive, and (4) hostile. The court of appeals ruled the homeowners had misconstrued the meaning of “possession”.

The Court of Appeals ruled the homeowners had misconstrued the meanings of “possession” and “exclusive”, stating “While it is not possible to be in adverse possession without physical occupation, [t]he ultimate test is the exercise of dominion over the land in a manner consistent with actions a true owner would take.” The City had granted temporary permits to the homeowners’ predecessors in title in the 1950s and 1960s for use as gardens and to access the road and did not prohibit the construction of fences or driveways. The Court of Appeals noted the City had maintained a continuous physical presence on tract 44 since 1951 and, although it consented to the use by third persons use for road access, recreation, parks, and trials, it nonetheless “managed the land as a true owner would under the circumstances.”

Therefore, the Court of Appeals ruled the City had adversely possessed all of tract 44, including the fenced in areas in the homeowners’ front yards. Next, the Court of Appeals turned to the primary question: whether the homeowners had adversely possessed their fence-in yards back from the City.

RCW 7.28.090 generally immunizes certain government owned lands (“lands held for any public purpose”) from a claim of adverse possession. RCW 7.28.090 was enacted in 1893 and has remained substantively unchanged since then. At the time, the common law rule nullum tempus occurrit regi was held to apply to certain government-owned land in the United States, preventing adverse possession by ensuring the limitations period never ran.

The Court of Appeals stated:

[…] the statutory phrase “lands held for any public purpose” means land actually used or planned for use in a way that benefits the public as shown by the benefits flowing directly or indirectly from governmental ownership of the particular property. To be shielded by the statute, the municipality must show some advancement of the public’s wellbeing from any part of the property. This is a fact-specific, reality-based inquiry that recognizes a single parcel owned by a government entity can serve multiple uses providing different public benefits, regardless of whether those uses are traditionally classified as “governmental” or “proprietary.” We do not decide the outer bounds of what actual or planned uses could provide public benefits, but we note that abandoned or forgotten lands put to no actual or planned use at all do not provide public benefits.

The homeowners argued the City’s use of the land for electrical distribution lines is not a “public purpose”, citing to cases which held the distribution of power by an electrical utility is a “proprietary function of the government.”

The Court of Appeals disagreed and focused on the historical use of the land for other purposes which benefited the public. The undisputed record showed tract 44 had been used for public recreation. When the City took possession of the tract in 1951, it allowed temporary permits for adjacent property owners to use portions of tract 44 for gardening and additional yard space. By 1954, a fish screen had been installed on tract 44 by the Washington Department of Game to maintain the trout stocked in Echo Lake for fishing. The City let sportsmen and “hundreds of children and teenagers” use tract 44 like a park to access Echo Lake for fishing and swimming. In 1973, the City and King County entered into a “permit agreement” providing for the creation of a public park along tract 44. The agreement authorized “recreational purposes,” including “picnicking, swimming, bicycling, and such outdoor recreational activities as are appropriate for a neighborhood park.” In 2001, the City signed a memorandum of understanding with King County and the city of Shoreline to dedicate a continuous area of tract 44 for use as part of the Interurban Trail.

The Court of Appeals ruled lands are “held for any public purpose” under RCW 7.28.090 when their actual or planned uses directly or indirectly benefit or advance the public’s wellbeing. It found the public had been benefitting from the City’s uses of tract 44 since the City took possession in 1951. The City has used its land to provide the public electricity and water. The City has used its property for public parkland and recreation, including swimming, fishing, picnicking, and bicycling. Because these uses have provided direct and indirect benefits to the public’s wellbeing, the City held the tract for “public purpose” under RCW 7.28.090, and concluded the City was and remains the owner of tract 44 in its entirety.

The Michel case demonstrates the nuances of an adverse possession claim and clarifies the Washington authority concerning attempts to adversely possess public land. Assuming the case is not reverse or clarified by the Washington State Supreme Court, it is a cautionary tale for any party who wishes to assert an adverse possession claim against property owned by the government.

If you or someone you know believes you have an adverse possession claim or have a neighbor asserting an adverse possession claim against you, please feel free to contact Chris Thayer at (206) 805-1494 or CThayer@PivotalLawGroup.com.